Katahdin Sheep Project Featured in Kentucky Afield

The New Range War | Sheep experiment takes a bite out of invasive plants

Kentucky Afield, Summer 2015 - by Lee McClellan

Bush honeysuckle emits a wonderfully light vanilla fragrance. While the plant's beautiful flowers light up fencerows, neglected urban areas and the understory of forests, it causes troubles galore.

Difficult to eradicate once established, this noxious plant forms dense thickets that eventually crowd out native plants. Bush honeysuckle refers to several invasive Asian species. Amur honeysuckle, a native of

China, is the most abundant invasive honeysuckle in Kentucky.

Cutting, digging and spraying all temper the growth of bush honeysuckle, but a new method of control may work best of all: chewing.

"We use animals with different types of diets,'' said Ed Frederickson, associate professor of agriculture at Eastern Kentucky University. "We can train animals to like certain plants. We want to teach them to eat plants we don't want."

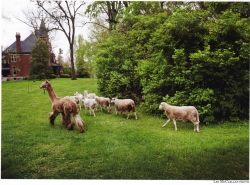

Frederickson relayed his thoughts while looking at several Katahdin sheep on the grounds of Richmond's Elmwood Estate, an 1887 mansion in the French Chateauesque architectural style now owned by the university. The sheep are part of a research project for an upper-level agriculture course.

Ted Herr, a junior agriculture major from Mansfield, Ohio, and Alyssa Paulo, a sophomore pre-veterinarian major from Shelby, Ohio, spread a portable electric fence around a giant growth of bush honeysuckle before releasing the sheep into the enclosure.

The bigger alpacas are trained to herd sheep towards targeted invasive plants. Two alpacas joined them to keep the sheep at the task of eating the bush honeysuckle.

The problem with honeysuckle is its bitterness deters cattle and many other grazing animals. However, Herr explained, "Sheep and goats have special chemicals in their saliva that block sour tastes and tannins. We can use animals to get rid of invasive plants and replace them with more amenable

plants."

The concept is called targeted grazing. "There is a big push for targeted grazing over chemical use right now,'' Herr explained. "The chemicals take out everything, both good plants and bad. Targeting grazing

takes out what you want to get rid of and leaves the rest alone."

Frederickson, who previously worked in the research service branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture for 25 years, said targeted grazing represents a potential revenue stream for farmers by leasing out their sheep for invasive plant control to other landowners.

Targeted grazing with sheep or other ruminant animals also allows facilities managers for municipalities, parks, college campuses and the like a way to control invasive plants on steep slopes unsuitable to control with manpower.

"The research on targeted grazing shows it will improve livestock pasturage to the benefit of wildlife,'' Herr said. "This concept can also be used on state natural areas and national parks."

Some day, perhaps, sheep will be the Weed Eaters of the future.

Published on November 16, 2015